As 2018 comes to an end, in an extract from the introduction to Mobile-First Journalism. I look at how the past few years have shaped the current face of mobile and social-native journalism — and what that means for its future.

The mood around mobile and social changed dramatically in 2018. To those working in the field, it could sometimes feel like being caught in the crossfire of a battle. Fake news, Russian trolls, concerns over filter bubbles and hoaxes, censorship, algorithms and profit warnings have all shown that the path to mobile-first publishing is going to be anything but an easy one.

Like any new territory, the mobile landscape is being fought over fiercely. But take a step back from the crossfire and you will see that different actors are fighting over different things, in different ways: and there isn’t just one battle — but three.

Journalism’s commercial battle

The commercial battle first erupted in 2013 when audience figures on news websites began to show some unusual changes: mobile visitors were starting to outnumber those on desktop.

At first this was just happening at weekends, but things accelerated quickly: within the space of a year mobile-driven activity dominated every day of the week.

News organisations concerned with delivering those audiences to their advertisers had to adapt more quickly than they anticipated to a mobile-first strategy.

The pioneering online publisher BuzzFeed went further than most: in 2014 it began hiring for a new BuzzFeed Distributed division, producing what would come to be known as “native content” — journalism which existed primarily on social platforms rather than on the publisher’s website.

Others followed suit, with some businesses built entirely on Facebook.

Elsewhere strategies differed: publishers began producing video in square ratio so that it would work on a vertical screen, invested in teams dedicated to chat and social platforms, and hired partnership managers to collaborate with their new ‘frenemies’ — the web giants that news organisations’ advertisers were fleeing to, but who they were still increasingly reliant on to distribute their news.

They looked to move into this new territory with journalists who could speak the language of social media, telling stories in different ways.

The political battlefront: the information war

Meanwhile, another battle had opened on a second front — and this one was political.

For as long as social media existed, there had been a cat-and-mouse game between protestors communicating via social media and authorities clamping down on the platforms being used: such was the case during the 2007 Myanmar protests, the Iranian elections during 2009 (when the US State Department famously asked Twitter to postpone updating its network so that its service would continue uninterrupted), and the events of the Arab Spring.

But in 2016 that information war entered Western consciousness too, and in new forms, as evidence surfaced of Russian attempts to interfere in the US election.

Donald Trump was to regularly use the phrase “fake news” to discredit critical news coverage in his own country, but it was fake news as a political tactic by foreign agents, alongside the use of ‘troll factories’ and fake accounts, that would come to public prominence.

Social platforms have been on the defensive ever since.

Facebook performed a significant U-turn when it announced it would be taking steps to protect election integrity.

Twitter identified and closed down 2,752 profiles believed to have been run by Russia’s Internet Research Agency — many of which had been quoted in the UK media as if they were real people. Then it closed down another 200,000 the following year.

And Tumblr refused to comment when BuzzFeed reported that it was also being used by Russian trolls.

This information war could prove to be the most significant for modern journalists: by turning our territory into a battlefield it risks turning us all into war reporters: verification skills are no longer the preserve of the hard-bitten hack, and information security is everyone’s concern when news media are a target for state hackers.

Culture wars

But it is the third battle which is most easily missed: a battle of culture.

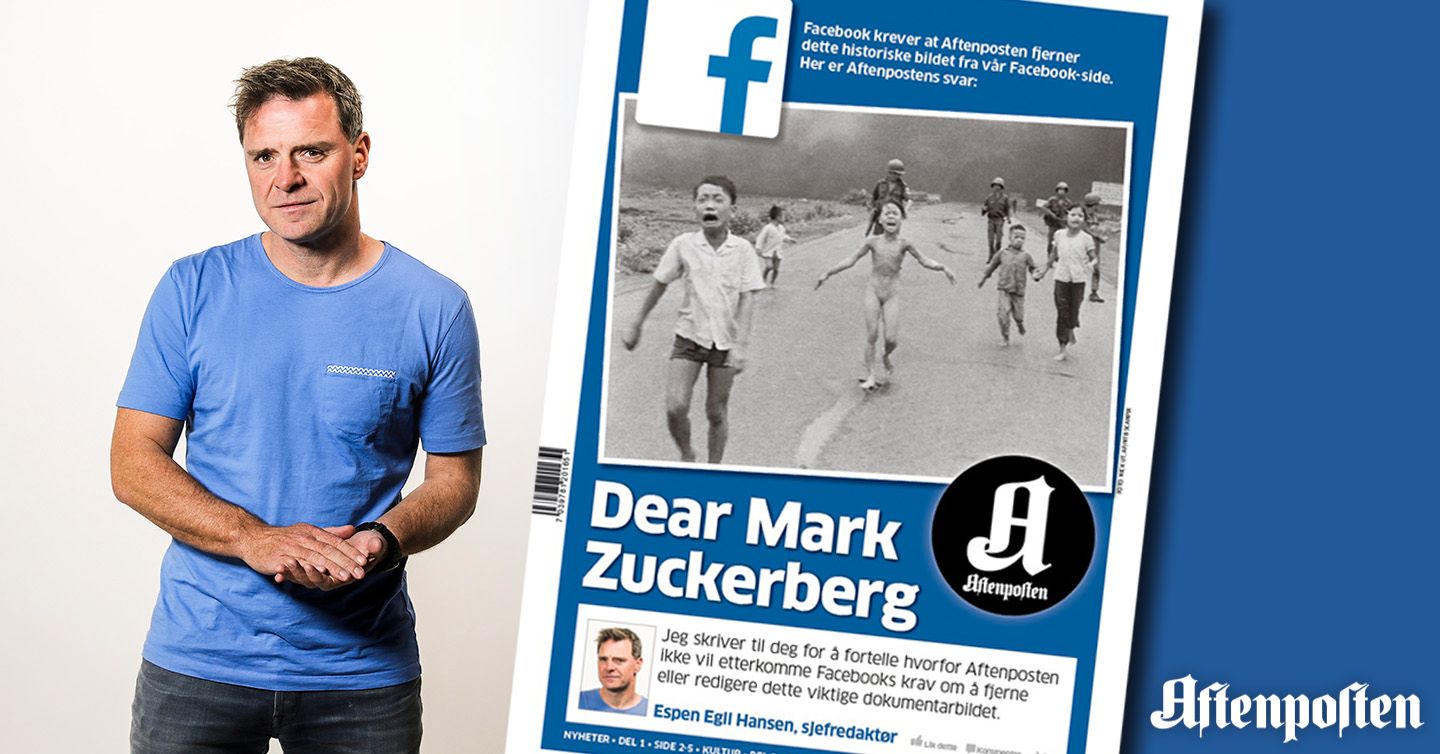

If there was an opening shot that was fired here, it may well be 2016’s open letter to Mark Zuckerberg from the editor-in-chief of the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten, Espen EgilHansen. In it, he responded to a demand from Facebook that the newspaper take down an iconic Vietnam war photograph by Nick Ut from its Facebook page.

“Dear Mark,” he wrote.

“You are the world’s most powerful editor … I think you are abusing your power, and I find it hard to believe that you have thought it through thoroughly.”

These shots have since continued to ring out from all corners. In early 2018 conservatives reacted angrily when Twitter froze or deleted thousands of accounts that it suspected of being bots, just weeks after the company had been accused of ‘shadow banning’ conservative accounts by downgrading certain tweets.

And social media companies have been accused of not censoring enough, as trolls use their platforms to target prominent female figures — including journalists — or incite hatred based on ethnicity and sexuality.

The cultural war affects journalism in particular because it is a fight to be heard, and a battle for relevance.

It is a battle that takes place within news organisations too: while some editors and producers struggle to maintain a system where news organisations still control both the news agenda and its distribution, many news consumers already live in a world where agendas are set — via algorithms — by a combination of friends, family, strangers and, yes, reporters; and where news does not begin and end at fixed times and spaces.

The cultural war is also a format war: the traditional inverted pyramid of newspaper storytelling has been overtaken by a proliferation of other shapes: engaging with a modern audience means engaging with new formats too, from the rise of visual journalism, live coverage and livestreaming, to gifs, emojis and memes.

Those who only speak in the language of the past risk losing the battle for the future.

Mobile journalism’s original promise

Of course amidst all this fighting it can be easy to forget about the original promise of social and mobile — the opportunity to bring a wider range of voices into journalism, and tell stories that would otherwise be left untold; to report from places and times that a traditional news crew could never reach; and engage audiences who would otherwise be disconnected from our reporting.

These promises remain as important as ever in 2018. And as the battles over money, power and culture come to a head, it is important to remember this: retreating to the old ways is not an option. We need to move forward. Mobile-First Journalism should prove a useful map to this exciting new territory.

No comments:

Post a Comment